Colloquio davanti le opere di Bruno Lisi – Marisa Volpi

Marisa Volpi: You told me that years ago you used to work with white: what was it that determined this transition from white to colour? Or is using colour the same thing for you? Bruno Lisi: I used white not to obtain the absence of colour, but to destroy it so as to obtain another one which would contain its echo and point to an ambiguity of «reading» in every sense, by emphasizing its unspecified distance beyond form and space. In some of your paintings, as in those of the «centrality» series, or in those in which there is this wave of light in movement, or in your most recent ones which have a vaguely illusionistic sense of space — even though it is not an emphatic, but only a barely accentuated illusionism — I notice that there are elements that lead to a symbology, although an intuitive and not an intellectualistic one. An echo of something, because your painting is always characterized as a kind of echo — an echo of an echo of something that is very far off and that is picked up by the antenna of your sensibility. The symbol is always present, irrespective of the feasibility of being able to «preconstruct» the symbolic image. It is present at the subconscious, archetypal level. Something that is, against your will. Is it the contest itself? Physically and spiritually? It’s the thing itself. But it’s not the protagonist. There are various types of mysticism: an uncontroversial, serene and contemplative mysticism, and a dramatic, conflictual mysticism. Yours doesn’t seem to be dramatic. By painting you attain, it seems, a kind of «peace». Yours, moreover, is a visionary, and not a veristic form of painting. The great aspiration is that of belonging to everything, of transcending the purely contingent. Art leads us — no matter what means the artist uses — far away from the quotidian. I agree with you that art is very far from being the same thing as craft. Yet there is an obvious common ground on which the two are forced to meet. There is within us an urge which I would call a «neurotic symptom to express something». Then there is the «project» that permits this something to go beyond the «symptom». And the «profession» in turn is the medium which we are obliged to work with to go beyond pathos, eros, mysticism, etc. Don ‘t you agree? The medium is always and invariably a pretext and a means which must aim at the overcoming of the professional skill and the restricting technicalities whenever these become protagonists in their own right. The creative magic moment, within the consciousness in which the project is developed, is the goal. After the liberation that you say was achieved by abstract art, can we really touch greater dephts, and freely express them in ways which bear no relation, however, to occasions of quotidian, historical or religious life? Other motives are finished: realism, because we have photography; religious symbols and iconography, because in crisis, and so on. On the other hand, the development of scientific technology seems to devalue the particulars of experience. Art seems to have lost just those characteristics that denoted it as such. Ars, meaning the capacity to make something with craftsmanship: the knowing how to make something well, whether it be a vase, a madrigal or a story. All this «knowing how to make something well» has been swept away, and naturally we find ourselves possessed by a great emotiveness, possibly stronger than that of our precedessors, who were undoubtedly less socially imbued with pathos than we are. And we have far less means at our disposal. Non-religiosity, in the sense of belonging, is the new liberating condition in the degree in which each of us succeeds in transmitting love in creativity, in which the absence of pathos is often concealed by professionalism. As part of this new reality, the recovery of a feeling of love is, I believe, the problem: certainly it’s mine. Art, moreover, has nothing at all absolute about it, and the communicative potential of an object is something relative created by the human mind. Precisely due to its intrinsic limitation, language has, in the concreteness of emotional, psychological, historical, philosophical and ideological life, no less moves to make in a more or less skilful manner. In the many moves you make you then find the one called art, which is nothing but the product of this effort of transfiguration which someone makes in tackling a material which has no intrinsic characterization on its own, and, by means of an enormous transformative process, finds a novel and original form. But contemporary man has nothing to do this with. You say he has science, but… science. You teli me that science is important? When I speak of science I speak of the ideology of science that adds absolutely nothing more to what is represented by the life of the body and its events, which are events of love, pain, sickness and death: a destiny similar to that of the plants and the animals, with the difference that man has a painful consciousness of it. And it is in this painful consciousness that beauty is revealed: the beauty of nature, of life, and of artistic creation. Science is this enormous and unforseen possibility of knowledge: of knowing what perhaps we knew, what we have always known, intuitively. It now forces us to ereater and wider forms of penetration, to better focused and less casual reflections. Paradoxically, the more we focus things, the more they elude us and refer us to that unspecified distance beyond form and space. It only remains for us, therefore, to counter the fascinating and challenging appeal to scientific analysis, to ascertainability and reproducibility, by giving priority — though not in opposition — to mysticism and illumination. At one time you did restorations of frescoes. How do you make use of this experience in painting your pictures? Fresco is the magic

A brief painting – Lorenza Trucchi

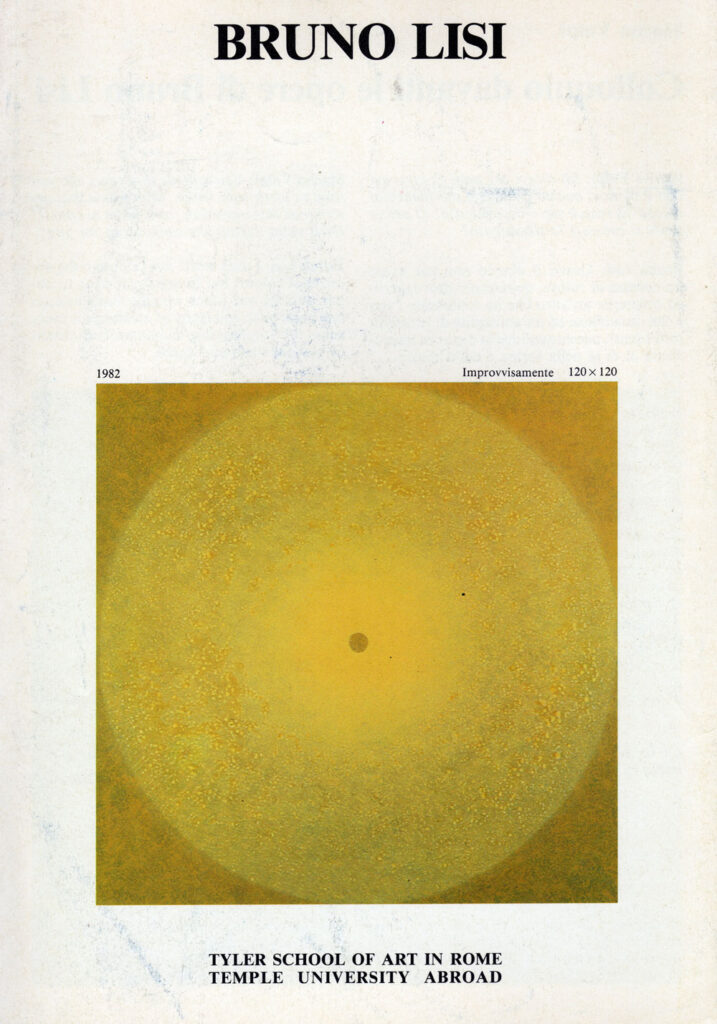

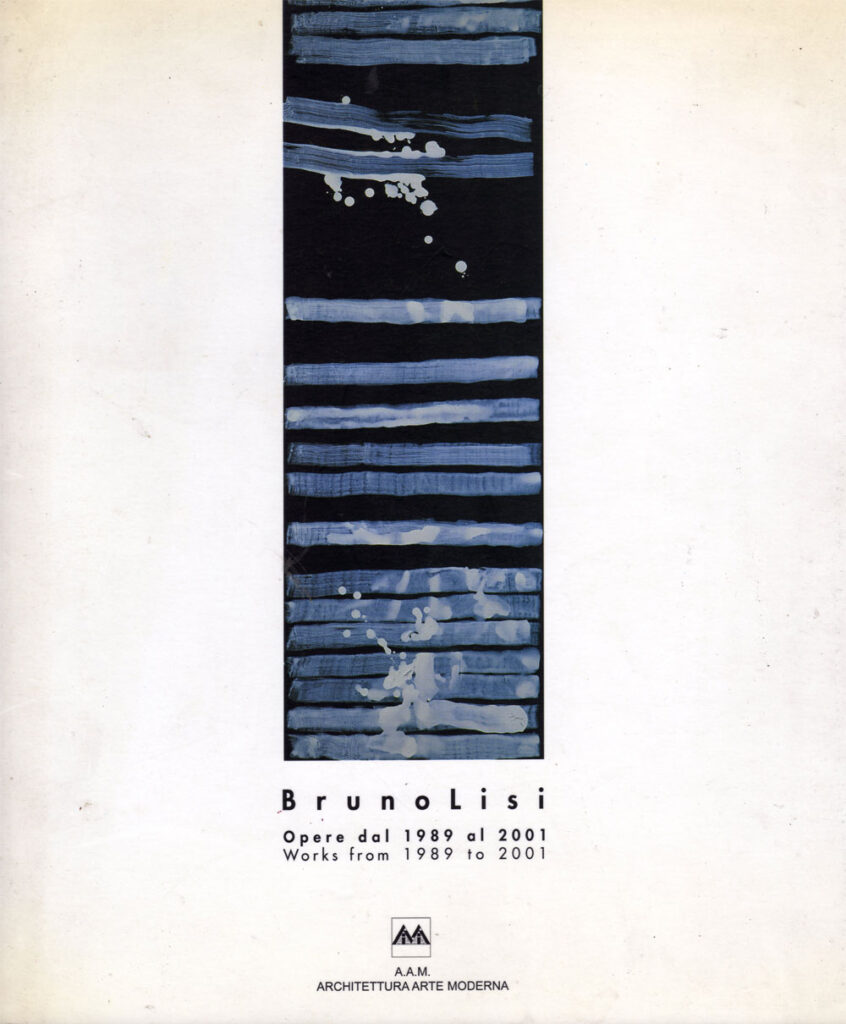

In the early sixties Bruno Lisi, just turned twenty, made his debut in a season moving rapidly away from the tired and rampant Informal. Shortly afterwards various other ways out were pursued: from Pop Art, noisily suggested at the 1964 Biennial Exhibition in Venice when object poetry exploded and spread from the Giardini di Castello and from the United States Consulate to Dorsoduro, to the more insinuating ones of conceptual and minimal art with relative constructive regenerations and strict diets that will bring about an elementary reworking of the glossary of painting, reduced to a monastic rule. In this climate that is more flottant than flou, without giving in to new and other fashions, Lisi turns towards a sombre but not severe abstract, based on uniform colour, on a thin impasto, giving a luminosity as intense as it is discreet. I don’t know if Lisi saw the splendid and well-timed Rothko exhibition held in 1962 at the National Gallery of Modern Art, but the show of the American painter should undoubtedly have been a lesson, better yet a stimulus to pander to his own substantially lyrical nature, and at the same time refining a routine of meditation, of nourishing silence. From then on, although his painting evolved in cycles and series, it always remained recognisable. Painting that stakes everything on surfaces but couldn’t live without the continual vibration, technically very elaborate (we mustn’t forget that Lisi is an expert at restoring and frescoes) of colour-light. Lisi intervenes in these spaces with moderation. He is definitely a virtuoso of brief painting, his often furtive images have the sharp effectiveness of apparitions, of absolute verses. A conciseness arising from modesty was reinforced little by little by daily exercise in concentration, so that today the path of the mental and emotional circuits strikes quickly, nearly a transfert, in gestures and in signs and images. These results are evident and surprising, above all in his works of the past two years. Large blue or indigo canvasses (I would like to call them skies because of their characteristic luminous air) crossed by wide brush-strokes of a colour that is more intense but not less transparent, actually aerial. One or two or three wide, irregular lines, stopping occasionally, briefly, then stretch out as though starting from far away after the prolonged encounter with the surface, and continuing on their way, leaving only the echo inside us. This gesture, generated by the unconscious and well directed by reason, thus becomes the subject of the painting. A gesture that invades the canvass in a fertile embrace. (translated by Helen Pringle) (from the catalogue of the exhibition: “Opere dal 1989 al 2001”, Galleria A.A.A. Palazzo Brancaccio, 26 November 2001-26 February 2002)

How to activate the way of viewing – Carla Subrizi

Having arrived at this stage in the history of art, after thesuccession or alternation of different definitions of the nature of art and painting, of what is a painting or what gesture or thought accompanied the pictorial surface, the current theory is that of transforming the question and re-thinking the artist-art dialectic. Thus the way of viewing and the point of view are at issue, not only of the artist but also of the viewer – that is, of those who participate in the relation and processes which instead of ending with the work of art begin with them, opening trajectories which extend beyond the immediately visible. The Sfere (Spheres – but the reference is also to the Italian word for ball-point pens) of Bruno Lisi, works which belong to a restricted period of his career (the second half of the 1980s), are important for the reconsideration of space and the sign or mark passing through it, without returning to superseded premises on why and how a painting or drawing is conceived or executed. What are we dealing with then? Abstraction or the final stages of a figurative representation which conserves merely the memory of something that is no longer recognisable? Are we dealing with ‘automatic’ gestures, with an echo of that magical split with logical processes as adopted by the surrealists, or of gestures evoking movement through space (of the futurist type), producing a synthesis between the sign that remains and the space which through that sign loses all balance and symmetry? Any answer would only deal with one aspect of Bruno Lisi’s work, while the Sfere are in themselves a departure from definitions which abbreviate in a single concept the multiple experiences of art and the thought that accompanies it. It must also be remembered that, in truth, the signs created by Lisi cross space in order to create tension, to reveal the vibration of images in space rather than to place these images in space, from the monochrome surfaces of the early 1980s or the tensioni di luce (tensions of light) of the mid-70s. The Sfere also emerge from a movement which is midway between randomness and the intention of depicting that particular sign. Bruno Lisi says it’s like the doodles one sometimes draws when chatting on the phone – you begin them but they continue on their own, while you’re thinking about something else. The hand begins a drawing which through a succession of variations and superimpositions starts to fill up the white surface, cancelling itself out and at the same time gaining strength, until it reaches the edges of the surface, almost as if seeking to escape it. The result is not simply an image defined in space (whether it’ abstract or not is no longer important), it is not just a sign in which to seek something recognisable, it is rather the activation of a relationship, of a tension which pushes beyond the image itself, producing a shift in viewpoint, towards the beyond of the image, its outside – the white space which has yet to be crossed. The Sfere thus depict an absence. They speak more of emptiness than of themselves. Not just the emptiness that surrounds them but the emptiness that is still inside them, of the consistency that they have lost, of a material which has returned to a more formless shape. They are traces more than signs, shadows more than physical bodies, they are what remains of something that has crossed space or is still crossing it – a trajectory which functions more as an indication of a direction to take (towards the outside of the space/surface) than a sign left by a completed journey. Looking at Bruno Lisi’s Sfere, Bacon comes to mind – a seemingly risky comparison. The bodies in the paintings of Bacon are figures in action, they push the movement outside of themselves, they communicate movement to the surrounding space, to the extent of producing dizzy rotations, centrifugal spinnings which deform faces and contexts, physically dissolve and melt body fragments until their remains are lost in space. Precisely because of this movement, Bacon’s figures imply that space is not just a context, that it isn’t just the surface on which the gesture is situated, that it is instead and above all a limit to be violated, a threshold to play with, a point of imbalance, where forces mix and dichotomies (inside-outside, internal-external, above-below) cancel each other out. This is precisely the tension which Bruno Lisi seems to convey with his Sfere, with the difference that a body, a figure, is not needed to activate the process. Lisi begins with an absence, a memory, a trace. Almost cancelling a section of space, he makes the force more powerful and with a simple gesture, repeated and almost without any subjectivity, irreversibly projects the potential of space beyond that which is easily visible. In other paintings, the same crossing of the surface – with such closely-positioned, parallel signs that no space is left for second thoughts or hesitations – is instead broken by scar-like markings, brief episodes in which the presence of an obstacle, an impediment is highlighted – a pain which has been dealt with but which rests indelible in the material of the thought/painting. Then these scars too become thresholds, zones in which to experiment with the loss of every certainty, in which the very certainty of always being able in some way to think and cross space wavers. Thus one idea is constant, and runs implacably and obsessively through all of Lisi’s research: the idea of the limit, which almost immediately becomes the idea of the void as a memory, of the image as a departure from that which defines it, of painting as an experience of something which is missing. Bruno Lisi’s paintings, and the Sfere in particular, aim to turn viewing around, to test it, to see if it is possible to imagine other journeys when contemplation of those already completed leads to

Writing in pure loss as the only way to write freely – Francesco Moschini

I have been trying for a long time to convince Bruno Lisi about the need to exhibit his work, at least the most recent work, in “unusual” places and in particular in some Roman “domus”, underground, uncontaminated by daily use, by excesses of light. That light all too enveloping, well known to those in Rome who are surrounded by it, clouded, then irreparably crushed by it. But this longed-for “different” venue for the artist’s recent works was certainly not motivated by consolatory searches for special effects, much less by a claim to legitimation induced obviously by the historical qualities of the places. It is the very condition of B. Lisi’s present artistic path that calls for the “historical need” to find again a hypogeal dimension in a kind of Heideggerian resetting of his work, almost to underline that not only man has to find again his own naturalness in pursuing a “poetic” life, but also that the work of man must aim towards this poetic aspect. B. Lisi’s recent works, going back again to the essential nature of two sole materials, the methacrylate and burnished metal filaments that animate it, seem to invoke a calming position that preserves them from the din of the noisy majority that today has pervaded the entire world of the art system. In this sacrifice of chromatic kindling by the artist, there is a real aim towards the cupio dissolvi, almost in, an extreme attempt to withdraw himself from any form of consumption and homologation. The spectral filaments can even slither nervously, imprisoned as they are in the material that fixes them in an unchangeable dimension; they can flow, open themselves, offer themselves and then drown, hurl down and then surface again, become so dense as to almost make a bundle of stalks like a votive offering, to then scatter without end, moved by a wind that has forced them to disperse. But this is only pure semblance: it would seem possible to disrupt everything with just a breath and yet the artist accentuates their vocation to show as figures blocked, frozen in a pursued condition of academic neoclassicism. It will be just the sudden bursts of light in a place filled with shadow, shadowy saps of some rare moss to give back a little fever to those sleeping figures. It will be their being crossed through by sudden lacerations, by unforeseen and unforeseeable gaps in that darkness where for vocation they would like to place themselves, to give back their life, but only to make clear that life is elsewhere. As in the phases of alchemic transmutations, the artist’s present path seems to concentrate in that extreme phase of the nigredo which isn’t the last one but is the one that lays the foundations for starting all over again. It is an invitation to “start all over” after the depths have been challenged, the bituminous excesses of the bottom, to discover, as B. Lisi seems to suggest, that writing in pure loss is the only way to write freely. Just like the Alpheus River which returns to its origins, the artist, nearly following, even though involuntarily, the instructions of Roger Caillois in Trois Leçons des Tenèbres, seems to humbly note and give voice to that exhaustion of sense for the unrestrained excesses of the growth of the sign. So there is no avant-garde nostalgia by using these “modern” materials, no desire for the future, as Dorazio’s research in Forma I seemed to indicate, though he made himself a “bard” of these materials, yet rather a solipsistic retreat of the artist to give a meaning, if still possible, to his continuing production of art, contravening the rhetoric question of Asor Rosa of “Scrittori e popolo” when he wondered about the meaning of making more poetry to reconfirm himself in his conviction of “how it was possible that words didn’t freeze in the poets’ mouths”. So, today B. Lisi goes to the roots of modernity and seems to find it again and indicate it in that crisis of the late eighteenth century classicism that sees Giovan Battista Piranesi wondering, on the altar of San Basilio in Santa Maria del Priorato, about the memory of the past and the need for things new. In that confrontation-clash between the rococo waste of the jubilation of the saint and the icy, crystalline beauty of the pure forms of the retro-altar, begins the liquidation of historicity in favour of an appalling yet superb idea of modernity founded on the “silence” of the form. This is what B. Lisi’s enigmatic, impenetrable suspension seems to suggest today, with his aphasia, with his superb portrayal of himself in a studied otherness. Yet on the artist’s part it is certainly not an indignant self-portrayal, rather a mellow return to the idea of the “book yet to come”, of the subsequent work with which to knot the strings again, of which the present phase is offered as an experiment of infinite entertainment. Though necessary to make those repeated filaments take the same flight to the elsewhere of the terminal metal summits with which F. Borromini concluded his domes, as in S. Ivo alla Sapienza where, as C. Brandi would say, the miracle takes place: the dome disperses in the sky with a final flash made of a few sinuous metal bars like “bird who first goes into a spin and then crashes and leaves light filaments in the air”. (translated by Helen Pringle) (text written for the exhibition “Cristalli d’acqua”, Museo della via Ostiense, Roma, in collaboration with AAM, 1-23 October 2004)

Painting as a stimulus/Painting as vibration – Francesco Moschini

As we were so used to the obstinate meticulousness of the “all full” of Bruno Lisi’s whole artistic itinerary, today it is really surprising to see him working on a new cycle that seems to have the dazzling rarefaction of the void as its foundation. To underline this apparent variation of direction of his search, he took recourse to a technique and a tool such as the ball-point pen, undoubtedly quite far from his customary predilection for a vibrant and pulsating painting, because of their being aseptic and their hinting at an indistinct and undifferentiated universe. But once again, for B. Lisi, it is a matter of giving body to unexplored depths, to bring figures subjected to tension to the surface, as if the whole work was treated in a “pictorial” way and not just the part where the sign gets thicker, clinging at and holding back the urgency of underground vibrations. That is why removing all trace of automatism from the mark, B. Lisi imposes a sort of faded chiaro-scuro on it that lends the image that has been drawn to the surface a vitalism, an animism and a sort of panpsychism that makes his search become more related with those theories on the universe as “seething” than with pure aspiration to form. At least this is what a certain baroque sumptuousness seems to indicate. We catch a glimpse behind those knotted and raised “curtains”, that “Ludovica Albertoni” kind of ever-changing material, stirred by the wind, but frozen by its being forced to emerge just slightly. A skeletal presence that survived the erosion of too much void surrounding it. So it is not by chance that as soon as these presences were evoked, B. Lisi cut them out and set them in a vertical sequence to create a real stele, impressing on the whole assembly, thanks to the clearness of the two white sheets placed in succession, an intentional archaicity that immediately declares its distance from possible memories of painting-painting. All this for a more suffering interrogation on the construction of void, on the structure of the figure revealing itself as it denies itself, in the abandonment of the hand that lets go and gives body and structure without a preconceived plan. The same dimensional exasperation impressed by the verticality of the work, that constriction to become pure poetic nook in the anomalous place on high of the various shapes, moved out of place in their most varied positions. They seem to measure the abysmal void that forces them to withdraw ever more into their shell. Then, more than a rapid passage of clouds, those apparitions seem to indicate a fear and at the same time a need to distance themselves from that void that made them emerge in the first place, in a continuous oscillation between desire to plunge in it and the fear of sinking in it. All of it in the certainty that their bursting in is guaranteed by the retreat of that void, by its opening up leaving ravines of accumulation of shadow if not of mystery. But to underline the substantial identity between the emerging figures, reduced to simulacre or rather finds in a stratigraphic excavation, that uncontaminated void though solicited by the slight telluric shocks that set in vibration those same shreds of image, B. Lisi adds to the rarefaction of this cycle a fast sequence of more intricate signs. A series of works where, more freely, the drawn sign superimposes itself, chases itself, intertwines with itself until it occupies every interstice. All this in a constraint to remain within the physical limits of the sheet, to not leave unexplored voids, almost to underline the distance of this mode of proceeding from going farther trustingly, from that desire to go outside the borders that was typical of J. Pollock, for example. And this enclosing inside a measured and controllable surface, making an effort to make sudden depths emerge only through the changing movements of the superimposed marks, or the discolouring of the various signs that intertwine, can only lead us to the idea that permeates B. Lisi’s work like a continual obsession from the sixties until today. This is painting intended as a continuing stimulus, a setting into vibration of the pictorial surface. And it is this very work on the surface, paradoxically, to register that search for inner depths and great spirituality that from the historical avant-gardes onwards has always characterised the way to abstraction. And these very sheets, with their obsession for an insisted mark always turning back on itself with its own circularity, recall that naturalism, forever evoked by B. Lisi as a fundamental element of his work, in the search for that “continuum where everything is”. Therefore it is not by chance, having underlined the distance between his work and that of the American abstract expressionism, the one that is more trusting in the “magnificent destinies and progress” of humanity, that B. Lisi tends to build a kind of logical connection with the extremely dense textures of vibrant microsigns by which M. Tobey expressed the incessant pulsating of life. What else is that excess of full, set against that dizziness of void, if not a remote memory of that “white writing” which, aside from the basic Oriental ascent, can’t help but present itself as a cognitive moment, or better a moment of pure reflection on reality? In the same way, writing across wide, luminous surfaces, as was already done in other cycles of his paintings, is for B. Lisi like bringing up to the surface fragments of consciousness from afar that the artist struggles to catch and translate into a new order that is not the intellectualistic or conceptual one, but the more familiar one of daily life, which is a continual projection of the present. In a sort of shadow theatre the irrepressible appearance of a universe led onto the visual stage, before it fades away, keeps us in the unstable equilibrium of precarious spectators of a

Figures in the shadows – Francesco Moschini

Finally a solitary, retiring and tireless artist like Bruno Lisi can retrace his entire artistic itinerary, or at least the last decade of it, with a retrospective at two exhibition sites. Palazzo Brancaccio is holding a review of his work from the end of the 1980s on, with large pieces representing each artistic period. The AOC, meanwhile, is holding a series of shows in which these various periods are examined in more detail. We can thus study the evolution of the artist’s work and, at the same time, focus on the sense of his insistence on certain themes, where an apparent tendency towards repetition is instead transformed into a patient search for unexpected beauty. The Palazzo Brancaccio exhibition, with its reference to the evolution of the work as a whole, helps us to appreciate more the “fixations” present at the AOC: the Stele of the early 1990s, with their taut ‘figures’ leaping out from the surface of the canvas; the layered Metacrilati which lend themselves to the exploration of body and lightness and body and mind; the Segni – “stacks” – which are slowed down and diluted with their allusions to the infinite, or concentrated to the point of becoming lumpy and lacerated, for example in the Otranto series; the Variazioni, where aerial lightness departs from almost abyss-like depths; and the Gesti, where wide-ranging, broad, decelerated, almost dragged bands alternate with the vitalistic phitomorfism of the “boxed” paintings, both stretched towards that dialectic between material and light in eternal unstable balance. Certain elements which have always characterized the work of Bruno Lisi are still present in this work from the last decade – the painful interrogation on the construction of the void, the structure of the figure revealed in its own negation, the letting go of the hand to give body and structure without a predetermined design. The constriction of remaining within the physical limits of the paper, of leaving no voids unexplored, emphasizes the contrast between this way of proceeding and the trusting going farther, the desire to pass over all limits which is typical of American abstract expressionism. Painting intended as a continual stimulus, or better a setting into vibration of the pictorial surface. It is precisely this surface work which, paradoxically, typifies the search for inner meaning and great spirituality that has always characterized the road towards abstraction. There is a constant tendency to reduce any presence inside the art piece, losing the colour and eliminating all structures which might hint at the search for a complex design – works which tend to create a place of minimum intervention using the void, the whiteness of the canvas, just barely stirred, slightly rippled, like wax furrowed by fleeting footprints of which only a trace remains. Bruno Lisi’s works also always tend towards pure and absolute knowledge of every form of objectivity, subordinating colour and structure to spiritual communication and pure idealization. In the most recent ‘bands’ marking the Gesti series the material expands, extends and becomes emphatic almost to the point of denouncing that its beauty can be fixed by love for things even while revealing simultaneously and wickedly the unfathomable void we could fall into if we were content with that extenuating, formally upright, kind of beauty and if that eternal reaching out for elsewhere did not support us. Various eminent critics and art historians have been asked to comment on specific periods of Bruno Lisi’s work. Through their analyses, which are not meant so much as philological criticism, as rather a general re-examination of the artist’s work, it is possible to propose a new theory which sees his work as the continual repression of – or better – progressive distancing from the obsession with reality. At the same time the artist must continually take reality into account, in order for his work to assume the character of a search for constant, sophisticated abstraction which allows the objective original data to re-emerge. What else were those first Stele of the 1990s with their luminous vibrations if not elements of a baroque movement, in which gusts of wind moved drapes, wing-spans, whirlpools, rippled earth, sea, sky? And yet their presenting themselves as sudden flashes of lightning tending to deny themselves, to disappear from view, modestly declaring their “cupio dissolvi”, where the desire to disappear was stronger than the coquetry by which they showed their exhausting beauty, stated all the same the sense of continuity that B.Lisi wanted to establish with the culture of the place, of the city where he happened to be working. The artist has frequently tried to root himself in his context with his creations, through recourse to elements which, as metahistorical categories, have characterized the art work in a city like Rome, thereby bestowing continuity on them and giving to his research a dimension of the “eternal present.” Some such elements of permanence can be detected in Bruno Lisi’s work – “agudeza”, “trompe l’oeil”, that is the ambiguity in perception, “sumptuousness” and other devices which form part of Rome’s artistic heritage, at least from the Baroque age onwards. But these elements are transfigured by Lisi to the point of becoming mere shadows of a past greatness now presented as pure fragments of a world no longer even dreamt of because stripped of all consoling illusion. In the Otranto series, those ‘wounds’ where the mark becomes thicker become the open declaration that even the exploration of the depths of the canvas is no longer possible – that spatiality of the beyond so sought after in the slashes of Lucio Fontana in order to obtain the most repellent and anti-beautiful appearance of things. Even the condensed mark, almost as if we are focusing in from a distance, recalls Domenico Gnoli’s obsession with close-ups but at the same time activates a mechanism whereby the viewer’s eye flees to the beyond, towards the edges of the work almost making it impossible to force it to focus on the centre of the piece. The anxiety created by these

The spatiality of passion – Enrico Mascelloni

Sometimes when you meet a person for the first time, you are instantly reminded of someone else, someone lost to the years and the space of continents. Bruno Lisi was just such a person for me. Before I had even decided whether I liked him or not, or reflected on my instinctive response to his art, my thoughts flew to a Portuguese man whom I had met some years before in Maputo, Mozambique. One might assume therefore that I liked Bruno immediately because I connected him with a friend from the past. But that wasn’t actually the case because I didn’t particularly like Cabral. I went round with him in Maputo more because I was forced to than because of any natural bond or shared tastes, although I was fascinated by his curious habit of expressing his thoughts but at the same time not expressing them, of alluding to something but remaining silent on the substance. Bruno’s clarity of expression, on the other hand, cannot be denied. And yet the likeness wasn’t just physical – it had to do with their way of looking at things, with a certain melancholic or distant smile, and perhaps something else which I can’t quite put my finger on right now. I became acutely aware of it one evening when I was invited to dinner at the house Bruno then shared with his wife Ida. Watching him commenting on the paintings and sculptures as if they no longer related to him, seeing him there next to his beautiful wife, I suddenly realised that Cabral, whom I had never liked that much, was a brilliant and likeable friend whom I would probably never see again but of whom I would preserve a keen memory – although, to be honest, my memory of Makonde was more intact. Makonde was a charming girl who every so often dropped in on Cabral bearing an array of strange and vaguely bitter sweets. It was that very evening that Bruno asked me to write something about his latest sculptures in methacrylate, which immediately struck me as intense but at the same time distant, non-material and abstract in the most meaningful sense of the term. The first thing that came to my mind, while I sat there sipping my coffee, was the title, which goes like this: “the spatiality of passion”. Then I wanted to remark on how the void had been incorporated into the actual body of the sculpture. Indeed, we are dealing with the transformation of a void into an object, a heavy form, which is as structurally impending as only a square block of transparent material could be. The rhythmic articulation of the methacrylate panels evokes a sort of multifold depth marked by transparent sections, a layered void, the paradoxical negation of its very self. A concrete cage where colour constitutes itself as a negation of emptiness and the undemonstrable offspring of the diffusing light that assails and invades it. The void coincides with the unsustainable density of the block and is transformed into heavy material through what the eye perceives as its layers of non-existence. And thus a work which would seem to be an apologetic celebration of the void ends by demonstrating its improbability. Then I felt the need to write something about Lisi’s older works. Lisi appeared to be fascinated by the nervous solitude of colour, to the extent of suspending every distraction which failed to coincide with the dynamic substance and movement that conformed to it. The emptiness of the white canvas highlighted the passionate skeleton, with its closely-woven, sharply-defined fibres. Only the structuring of emptiness could convey the wrenching solitude of colour and all its consequences. Lisi originally created the three-dimensional articulation in small formats (in polypropylene not methacrylate) which experimented with the efficacy of a new spatial organisation of colour, later to be fixed in the sumptuous “invasiveness” of the blocks of methacrylate. Thus the methacrylate structures are not just containers of colour – they sublimate its ironic encapsulation, leading, in Lisi’s latest works, to its transformation into Nature. The spatiality of passion, which fermented between the folds of chromatic dynamism, lends itself to the paradoxical estrangement of the transparent block transformed into ‘landscape’, that is, a guarded structure protected from all forms of ideology, even an ecological one. The void therefore becomes a trick of form, pretending to be split from colour but in reality acting as a frozen bed on which it can manifest itself in all its most unpredictable aspects, to the extent of recovering with unexpected poetic shivers the most exploited image in the whole history of art – the landscape. That was how my piece ended. A long time passed before I saw Bruno again. I bumped into him in Via del Babbuino with Irene. He asked me to publish the piece I wrote back then in his new exhibition catalogue. I told him he was free to do as he pleased with the article but immediately added that I would prefer to edit it slightly, given the time that had passed (if you don’t look time in the face, it shoots you in the back). Seeing him with Irene, I immediately thought how women are able to mark the rhythm of life, giving it the cadence of their presence and if necessary their abandon. My thoughts again returned to Cabral, to Makonde, to Leinita in Maputo who would never give me her real phone number, and Ida – whom I never saw again. I lit a cigar and started walking towards Piazza di Spagna… (translated by Michele Von Büren) (from the catalogue of the exhibition: “Opere dal 1989 al 2001”, Galleria A.A.A. Palazzo Brancaccio, 26 November 2001-26 February 2002)

Bruno and Bill – Massimo Martini

Friends and editors were chatting about the new catalogue of Bruno’s works. And they started “fishing” in the web of his lifetime. Smiling, but not too much. “…horrid man wearing spats, insult me in the square, play havoc with me, so I can be recognised, the next day, and the next, like the one who…” It would have been the height of snobbery for a bashful and pure painter. And a shrewd critic just says: … sublime art transcends vulgarity… But these are slippery times. And when Irene remembers how Bruno was about to be chosen as the young actor in Truffaut’s “Les 400 coups”: – it seems like an exam for everyone – everyone looking for connections – in that chain of certifications that leads to Calvino’s knickerbockers – that – together with Pavese, Einaudi and our man – plus a faceless fifth – is leaning against a low wall with an out-of-focus view of the Langhe countryside – that very docs of docs – that closes the circle of cultural desires. Pause. We know for sure that Nada Malanima loves Bruno’s painting. We also know that we are alone in this valley of tears. And that Nada took flight, hung from a steel wire, moved by a Nobel prize. While Rome is falling heavily on us. Coffees go round. Irene gets up, goes home, turns and looks back, says to Bruno: come here, Valentino Zeichen is on the phone. (Valentino, just like the great Mazzola.) Waiting for a painter – kind of short – with lively eyes – from the north – who makes tiny, tiny paintings – abstract paintings – that he sells for a hundred thousand lire each – so he can make a good enough living this painter nearly whispers – we knew that art is a convention that follows set rules – we knew that the road to change these rules is impassable and glamorous – but no one told us of the pain in keeping within the rules. The pain in keeping within the rules. Night. Keeping the light-hearted words of the painter of the tiny, tiny paintings in the basket of pride. But the next day there were other things to think about, such as the strong north wind, that cleans the beach of debris and gives a clear view of the islands, large and small, across the way. News. Producer Amedeo Pagani engaged Bill Clinton for a cameo role in his next film by Theo Angelopulos. During a brief stop in Rome, during the former president’s trip to Athens, a visit to Bruno Lisi’s studio was planned. Full stop. – my dear President, please come in – it is an honour for me to pay a visit to an artist I don’t know, and I’m sorry to have taken such a long time – rather than pay a visit to me, I prefer you to look at my painting, piled here on the floor – when I see paintings on the floor I have doubts, anxieties and uncertainties – this may be my only defence when faced with a confrontation… you see – but I do like clear and open relationships, tell me Bruno, what is your kind of painting – I paint colour pause – it seems to me that you paint material – then let’s say that I paint material that brings colour – let’s say, material that by convention is considered colour – the one in the tube – nothing more than that pause – you have convinced me: I paint material because of its being colour – the brush is, we could say, ascetic in your work – the brush, as you see, takes its own advantage – that’s true, it’s at the centre of attention just as one who officiates at rites – ask me no more, I’m not ready to become a conceptual – come now, cross the threshold, abandon that material that you already call immaterial colour – goodness you’re cool, you’re really cool, Bill pause – what can I do for you, Bruno, more than thank you for having received me pause – send me some capers from Greece – did you say capers – yes, I said capers pause – OK for Greek capers and… ciao Bruno – ciao Bill Pause. Pause. But Bill’s forward flight into the atmosphere didn’t lessen the solitude of the occasional writer. That casual word kept appearing: “conceptual”, a candid provocation which came up out of the instincts of a lunar conversation. Work could be done on it.ì How. Maybe like this. 1- I don’t like to describe the effects of a gesture when the gesture is explicit. 1’- And… I’m not interested in looking for secrets in instigated chance happenings. 2- Everything in Bruno leads to an explicit gesture, mostly a “slow gesture”, that “comes and goes”. 2’- And… such a clear situation as to look like there are no ways out, in an elsewhere of meaning. 3- John Cage says: “Let’s say he isn’t a Duchamp. Turn him upside down and he is.” 3’- And… Sol Lewitt: “The meaning I give to the term conceptual art has something to do with the way artists work and it tends to emphasise the idea rather than the result.” And therefore. Leaving each reader to imagine how. Why not prefigure, starting right now, the day in which. Accepting an expanded destiny, well beyond Benjamin as is already customary. Bruno, poised in mid-air in the little fig-tree square outside his studio, right near the telephone wire where one summer night a rat lost its balance and fell onto stunned and disgusted dinner guests (who then executed the rat). Bruno, like a new Christ, like a new Christo, turning to his multiple disciples who have come from all over, in the act of raising his painter’s hand, murmuring in blessing: “…go and repeat in my name…” (Translated by Helen Pringle) (from the catalogue of the exhibition, “Opere dal 1989

Bruno Lisi’s net of signs – Francesca Gallo

Around 2009 I began a more regular association with Bruno Lisi (Rome 1942-2012) and the Associazione Operatori Culturali Flaminia 58 (AOC F58) of which he was president. AOC F58 brings together a small community of artists with studios nestled in the Borghetto Flaminio, round the corner from Piazza del Popolo, in Rome. They have been running regular exhibitions since 1988. When I visited, I would often find Bruno attending to some new work (a collage), with a scattering of magazine cut-outs, not yet pasted, against the white cardboard on his desk. A lot of them involved segments of women’s heads of hair, typically brunettes, which he rendered almost abstract by combining with other collage elements amid intricate patterns penned in Indian ink. While his application to scissors and paste was reminiscent of the cutting in colour of the elderly Henri Matisse, the dissection of female features had about it something disquieting, even when they became almost unrecognisable in the finished works, as we see in the series Corpi estranei (2008-2009), to which Patrizia Ferri refers in terms of energy agglomerates and tattoos, and Senza titolo (2011-2012). From the vantage point of early observations that were essentially fortuitous and subjective, a tendency to linearism emerges in Lisi’s overall production at the root of which is some feminine detail: it is from such intuition that these notes develop. Trained at the Rome Istituto Statale d’Arte under Alberto Ziveri, Lisi began with works in which abstraction and figuration coalesce, as Cancello verde (1962) suggests, just as the impetus of Arte Informale was spending itself. The works he brought to his early solo exhibitions, in the early sixties, were investigations of the female body: squarely and plainly rendered, at first, then elusively evoked by mere hints, with the anatomy serving almost as pretext. In the accompanying text to the 1969 exhibition at the Galleria 88, in Rome, Venturoli spoke of paintings that tend towards a «monochrome palette, something between white and pink, which has an unmistakable suggestion (or memory) of the nude». This fidelity to the nude, a canonical theme in painting and a mainstay of Lisi’s production, was to lead to especially accomplished works in the seventies. In Figura nella spiaggia (ca. 1964), the nude is foregrounded and the painter indulges in sustained observation (while himself remaining, perhaps, unseen). This same impulse to watch closely is at work as the artist lingers on a curled-up and faceless body (Ritorno, 1971), then homes in on more detailed views: an eye, or mouth, and finally on certain ciliate entities – seemingly a combination of lips and labia, or cells on a microscope slide (Senza titolo, 1973-74). Such proximity of observed and observer could read perhaps as a pornography of the gaze in which the inspection occurs at close range, seeks to explore beyond the bounds of the visible, and surveying devices probe deeply and trespass all dark recesses. As such, this viewing impulse is certainly a male trait; as it is also constitutive of a social order in which everything from biomedical technology to public surveillance systems is geared to ensure total visibility. Besides, female lips, mouths, and smiles had been canonical with those artists whose work was modelled on the advertising world and serialised poster images. Visual poets like Luciano Ori and other artists like Umberto Bignardi took due note of cosmetics ads and incorporated them into their art. Then there came such alluring, singled-out details as in Pino Pascali’s Primo piano labbra (1964), or, in the same year, the great lips in Claudio Cintoli’s mural Giardino per Ursula, designed for Rome’s Piper Club. Pascali further rendered an Omaggio a Billie Holiday (1964) with projecting lips, whereas the Lips sofa designed for Gufram by Studio65, in 1970, came with its promise of seductive home comfort. Not to mention the ironic irreverence of John Pasche’s tongue and lips logo for the Rolling Stones (1971), echoed visually in Lisi’s profile of tongue and florid lips (Metamorfosi Virus, 1972), though tending rather, with Lisi, to spontaneous or erotic posturing than cheekiness. It is no surprise that the early seventies should find Lisi in thrall to the almost obsessive spell of a young woman’s lips. With forerunners in the creations of the Rome pop art milieu, but decidedly more eroticised, Lisi’s mouths incline towards Hyperrealism, with a glossy, reflective varnish that openly declares itself as paint and droplets of colour in semblance of saliva. Eschewing the mediation of photographs and transparencies (characterising, instead, the modelling of art on serialised media images) Lisi’s mouths stand out as life drawings based on the real. At about the same time as the sensational mouths (a synecdoche of woman, one might say), Lisi was working on eyes that are just as flamboyant and have a faint outline of lashes (there are five serigraphs on display, from 1971). These lashes and, slightly later, the fine hairs contouring the ovoid entities in the series Senza titolo, 1973-74 (see above) came to morph and into their own, we might say, as the wiry lines that formally define the series Stele (1989- 1991), in coloured biro pen; or to elongate, in a more disciplined manner, in the richly diversified array of Otranto (1993-1994), with the sea-waves, beaches, wind-carved boulders, and ploughed fields of a part of the country to which he was deeply attached. His linearist aesthetic continued into the variations of Segno aperto (2003) and Tensioni (2004), where metal wires flow fluidly, congealed in the square-angled blocks of transparent acrylic resin, like living organisms crystallised in amber. Over the years, Lisi kept innovating, and yet his output remained slightly asynchronous from the current trends, following an independent and solitary course. Taken in its entirety, one senses the play on variations and allusions form a continuum as his apparent subjects range from observations from nature to dissections of the human figure so closely viewed that the resulting image is at times uninterpretable. Thus, the series Senza titolo (1972- 1973) and Senza titolo (1974) reach, we

Water crystals – Patrizia Ferri

Bruno Lisi’s artistic path culminates in a series of large rectangular canvases and methacrylate sculptures: mysterious objects that spontaneously relate to architecture, breathing in synergy with the whole. Totem-like geometry of absolute light that surfaces from an original immersion in the primary depths of language, sensation and life, like enigmatic ghosts, natural and suspended epiphanies coming from a virtual world, from a space where time has stopped. The results of a radical search for pure, zeroed beauty which responds to an ethic of one gaze, according to an intense, incisive, lyric and radical interrogation about the signifying void inside a lucid project. An operation of oxymoron and crossbreeding, yet at the same time of discipline and harmony oscillating between form and its negation, method and its disruption, reflecting on the present condition of the order of a world that rises in unbalance and instability, landing in the complex and mysterious atopy in the condensation of past memories projected into the future. The artist’s capability to abstract himself from reality is similar, in certain aspects, to that of the Oriental calligrapher, including his way of intending his relationship with reality through a lifestyle that sees art and daily life as exercises in spirituality, and considers context as a continuous, fluid transformation of energetic processes, like an open system, in continual transformation. According to Lisi, the void is a multiplicity, a dialectic web that doesn’t exist in the pure state — unrelated according to the metaphysical theory —from which it takes and expresses aesthetic potential, as well as dynamic and energetic ones, sounding out from near the nexus between the relative forms and sources of the void, so that it changes from a simple concept into authentic productive energy that manifests itself in the work in a sensitive, unmistakable way. A process entrusted to a sign as subterranean intensity, made of vibrations, oscillations to which the artist entrusts with exemplary ability the fundamental passage of beyond the visible, and the appearance of things, overcoming the instinctive tendency to recognize, to search instead of to know. Complexity as such raises uncertainties and questions about the search because only in the margins of open doubt and suspension is it possible to look at the future and meditate freely on the past, moving the dimension of creative work from axioms to relationships. “If man didn’t vanish like Adashino, if he didn’t dissipate like the smoke over Toribeyama, but stayed forever in the world, at what point would things lose their power to touch us! The most precious thing in life is its uncertainty.” (Kenzo, “Moments of Leisure’). Sign research in art, from the informal onwards, is characterized as the unhinging of linguistic and philosophic categories, as well as the outward extension of the author’s spiritual life since it is closely linked to the intensity of individual experience, in the involvement of various levels of experience. In the relationship that this latter establishes with the epoch, the need is stressed to restore reason and function of art: Lisi’s signs condense the saturation of meaning with minimal synthesis since they are lyrical traces and calligraphies of the soul that existence takes form in, they are exemplary, extolled, filtered through the conceptual sieve and at the same time faithful to their natural, phytomorphic nature, evocative of waters and skies. Traces of an incisive memory of nature and painting, a kind of ikebana that suggests the substantial transience of branches, atoms and thoughts, rocks and truth as a sole real condition through which to pluck the beauty of non-permanence, which is the real, intrinsic one of life in a broad sense. Those signs that transmigrate from the crystallized canvases in metallic filaments blocked in a dimension of immutability and together open to a thousand vibrations, twisted, spectral stalks, immediately come to life lighting up for a ray of light that crosses through them in the transparent methacrylate structures, like fossil signs of an internalized nature that surfaces from deep layers ofbeing, brought to light and transposed in the void, in the immaterial as though to operate a kind of last, strenuous safeguard. From the zero degree of a sensitive absence, with his ability to exalt intrinsic and metaphoric values of materials, Lisi points out through chilled, luminous presences, silent and enigmatic in a balance between being and nothing, that if life today more than ever is elsewhere, the artist’s duty is to bring it back here and now, illuminating it with tomorrow. Lisi’s fascinating, silent and unreachable works open a passage to the flight of imagination, to the deep sea of being in the empty space of infinite possibilities and desirable world to be reached through art as a legendary space for the imagination and, once again, the difference. (translated by Helen Pringle) (text written for the exhibition “Cristalli d’acqua”, Museo della via Ostiense, Roma, in collaboration with AAM, 1-23 October 2004)

The blue paintings – Patrizia Ferri

Bruno Lisi’s BLU – mysterious, visionary, solemn, pure. Years later, I behold it again and discover intact tense and absolute sensations that spring from the depths of the soul. Fatal oceans, turning tides, skies full of violent darkness and glassy, metallic lights, lazuli corals, sponges and seaweed, clouds and air, cosmic breaths, the fragrance of infinity, authentic spaces of illumination where it is possible to cultivate the certainty of constant, absolute doubt and precariousness, expectation and perfection, peace and solitude. Paintings with a blue and harmonic aspect, pervaded by flashes of suffused uranic light, by luminous breath, an unreal aura of visual Nirvana in a world of people and things that are mostly serial and self-contained. They speak the language of meaningful emptiness, a peculiarity of both Oriental philosophies’ interior exploration and the radical line of painting. Giotto’s blue skies, Kandinsky’s abyssal resonances, Klein’s Blue dipinto di blu with mille bolle blu from his playful and esoteric universe…. Blue as in a quintessence of art’s energy and spiritual value, not just as an aesthetic product but also, and above all, as an act which creates and qualifies the relationship with others, nature, things and everyday life and that involves a deep spirituality – not transcending but at one with reality. “… I don’t begin by thinking in a rational way ‘now, I’m going to paint a blue painting.’ Instead, it is the blue itself which seizes my hand and at that point, I let myself be overwhelmed,” Lisi confides. It amounts to emptying out one’s mind, heart and body; allowing this particular dimension to manifest itself in the full objectivity of the work and “reawakening” the awareness of one’s own void as taught by the Oriental philosophies of impermanence. The artist knows that to practice the aesthetic of the void means advancing along the path of no return in the search for pure pictorial form, not in a speculative sense nor that of pursuing conceptual value, but fulfilling the experience of the void as an energetic principle inherent in time and space, something that has fascinated and inspired entire generations of artists, revitalising experimentation and the language of art in the broadest sense. Lisi’s BLU appears at the end of the 1970s, permeates the Sincroni cycle during the mid-80s, then recedes only to reappear in the second half of the following decade in the anomalous wave of the Variazioni, an installation – open to the influence of the place it occupies – of condensed, rectangular spirituality, windows on the geography of the infinite, leaps into empty space, plunges into the depths of humanity and of painting, freedom zones. The comparison with music is inevitable since, together with painting, it is the expression closest to the spiritual life of the artist, to “his inner needs” as Kandinsky put it. To emphasise the peculiarity of colour, Kandinsky would talk about a man from Dresden whom he described as one “endowed with rare spiritual gifts who always and unfailingly felt the taste of a certain sauce to be ‘blue’, or rather he perceived it as the colour ‘blue’”. Kandinsky believed that such a faculty belonged to highly evolved beings gifted with direct access to the soul through the senses, a phenomenon that he compared with resonance in the field of music. The essential point today is that art must return to stimulating and springing from emotion, that is, the work of art must become the vehicle for establishing this extraordinary equivalence – which cannot be put into words and cannot be forced into a concept – which suggests the complex, unintellectualised experience of reality. Art should silently evoke the mysterious and unfathomable nature of life beyond appearance and the coexistence of opposites, the indissoluble link between the search for the immaterial, and material life, in the direction of beauty. Painting, like music, writing and other art forms, stems from the need to communicate among individuals, to express the depths of one’s being, as Gao Xingjian, the Nobel prize winner for literature, has stressed, with typical Oriental essentiality. He analyses the crucial issue of aesthetic sensibility in the East and West through intrinsic analogies between ideographs and painting: “The visual arts have used various expressive and representational means to disclose the real world, dreams and chimerical visions and, via the abstract, have opened up space for feelings and inner visions which reach beyond the intellect and concepts and cannot be dissociated from sensitive experience. To get to the places where reason is incapable of arriving, one must turn to art.” Lisi’s cold and incandescent BLU is born from the desire to create only paintings that are necessary, works which are necessary and vital and can therefore be experienced through all of our senses. They are an enigmatic and reassuring presence, pure, spiritual expressions of an artist gifted with intense and far-reaching sensitivity. Mysterious, visionary, solemn, pure. (translated by Michele Von Büren) (from the catalogue of the exhibition: “Opere dal 1989 al 2001”, Galleria A.A.A. Palazzo Brancaccio, 26 November 2001-26 February 2002)

Art under his skin – Patrizia Ferri

Lisi is a ‘threshold’ artist, a poet of the radical void that cultivates cyclic and imponderable obsessions that in sudden and rhythmic waves and romantic undertows alleviate from the unbearable weight of existence. His signic search, in its variables in time, surpasses the identification between art and life and the distinction between conscious and unconscious: it does not represent, it does not express, it simply manifests a continuity between itself and the world, expressed in terms of difference between magnitudes and quality of tensions, in the synergy between gesture and sign of informal derivation, relating the dynamics of the physiological microcosm and the cosmic macro space. The beginning of each cycle of works is not planned, and it expresses a sort of regeneration, a true aesthetical and existential rebirth according to an idea of art that continues to question its intrinsic reasons and its function, beyond the assertive logics of meaning. In the “Alien Bodies”, the latest cycle (time wise) unseen so far, the sign is a sensitive, irritable string, as a nerve ending that creates tangles, vacuum energetic concentrates, imploded phenomenologies, energy blackouts of a highly concentrated spatiality, concretions, alien bubbles, the quintessence of worlds where mysterious events take place, kept inside the page margins that, like so many daily short stories, tell all together about a life that was let go moment by moment, as in the Oriental meditative methods, for which Lisi manifests yet again an absolutely natural aptitude. The sign is a philosophic and physiologic conductor, as an author’s appendix, but also as something other than himself, where crossbreeding with the image produces symptoms of alarm and arrhythmia in an occult, mysterious tension. The “Alien Bodies” are tattoos that sensitise the artist’s being in his contact with the world, a contact that lightens and becomes bearable, manifesting without revealing the deep sense of life as a dynamic cycle in its intrinsic reality of expansion and regression, evolution and involution, development and stagnation, systoles and diastoles, following an attitude that substantially expresses the capability of letting art get under one’s own skin. (translated by Helen Pringle) (text for the exhibition “Corpi estranei”, Galleria Miralli, Palazzo Chigi, Viterbo – 24 May-7 June 2009)

Segno – Cecilia Casorati

According to Ludwig Wittgenstein, contemporary philosophy can only really be concerned with language. If this is true of philosophy then, without wishing to seem to state a necessary truth, it could equally well apply to contemporary art. As in every apparently closed system, even that of art will have as its origin, object and probable goal the linguistic experimentation of its means. In his celebrated book Le degré zéro de l’écriture, published at the end of the 1950s, Roland Barthes called for a sort of new Revelation of Literature (a wish paradoxically sceptical given its enclosure in a Utopian space) which was preparing its advent through a form of writing that had shifted play to a neutral ground. Writing – and obviously art too – was, or at least appeared to be, in a sort of cul-de-sac. On one side, it had at its disposal a body of rules and conventions (The Legend of Literature) which distanced the writer from the present. On the other side, should the writer desire to open his writing up to the “current freshness” of the world, he could only make use of a “dead and splendid language”. The tragedy and instrumental inadequacy of the artist before the world was tackled from the 1960s on using “neutral” linguistic methodologies which we all know as conceptual, minimal and pop art. After the 1980s, during which time neutrality was again mixed with the languages of the “past” giving rise to anachronistic and inconclusive elaborations, more significant experiments emerged which tried to revitalise back to neutrality the dead and splendid language of art. In the Utopian sense, Barthes held that the problem of writing, after its sojourn in the neutral field, would be resolved through a superior moral work leading to a “universalness” in which writing and society would be capable of living together in a uniform way. More realistically, and with the advantage of time, the artist – unable linguistically to achieve the “freshness of the world” and the alienation of history – decided to reinforce the autonomy and separate identity of his own linguistic system, reformulating it in a transitive way. In the works of Bruno Lisi – and in particular the Segno series from 1993-2000 – the linguistic problem manifests itself essentially as the search for expression. Expression of the form which is constructed or veiled, however in this case both terms are actually pleonasms since there is neither direction nor track in his works, but rather the deliberate will to represent a movement. In such a way, signs and images detach themselves from a coercive system of pre-established meaning, proposing themselves not as idealistic models but as mere appearance inside a linguistic circuit from which, with some worry, one tries to snatch out a word to come. Without getting lost in exuberance and hyperbole, Lisi uses his modern conjuring lamp, probably showing that elsewhere – made of memories, “linguistic tricks” and mental associations – which is not legitimized by the rational order. One of the essential elements of his work appears to be construction, intended as a balance between sign and language. His works are not just clearly defined intuitions, inventions that are subtle and essential from a formal point of view. They are above all peculiar and intelligent statements, obstinate affirmations of the autonomy of art. Things, objects become separated from their usual relations and become signs, traces which the artist gathers and recomposes, creating another reality, closed to the ordinariness of meaning, the arrogance of sense. Lisi’s artistic language – which is both solid and light at the same time – asserts the contemporary artist’s possibility of continuing to exercise, in his own metaphysical reserve, the “linguistic” rights of utopia. (translated by Michele Von Büren) (from the catalogue of the exhibition, “Opere dal 1989 al 2001”, Galleria A.A.A. Palazzo Brancaccio, 26 November 2001-26 February 2002)

The contemplative edge – Camilla Boemio

The exhibits offer an opportunity to be seized in a tough time, like the one in which we are living. The confinement, the circumstance of subsequent conditioning, and the mutation of the rituals of the art world have brought a singular appreciation of the system, with a hunger for art projects which can reach people, offering them new interpretations from a dynamic perspective, and a rigor and awareness that restore a freshness to the mechanism. As Claire Bishop clearly explained in her essay on radical spectacularization in museums, the latter are ever more intent on taking and disseminating images, in-depth analyses, and interviews. We are at a critical point for how museums think about themselves and enter into the fabric of communication. It is increasingly necessary to be part of the enjoyment as producer and actor in the staging and as the primary cultural subject and object. There is a new present to build in which the contemporary becomes a supporting structure, able to influence and reach people. It is an apperception of reality in the making in which every challenge becomes the great challenge to overcome. From this perspective, Bruno Lisi’s exhibit becomes an opportunity to dialogue with the antique art, to reintroduce us to the most prolific decades, between the 70s and 80s, of Italy’s capital city. This period is established as one in which art in Rome became the construction of the myth; an opportunity for the retrospective that celebrates an artist in his chimeric practice, whose elements of pictorial process are considered and discussed. In time, the light characterized Lisi’s research in nonlinear permutations, notable for both their presence and absence. The urgent luminosity has migrated in his ample practice. His paintings possess a newfound clarity and purity of color, as well as in his drawings which are imperceptibly nuanced in color, reminiscent of the fact that sight is a corporeal phenomenon in which the eyes register palpable energy. These prismatic effects, evanescent, are nevertheless compensated for by the transition rendered in earthy registers that give weight to the most luminous colors, giving the impression that they grew organically from the metaphorical “land” of the chromatic spectrum. In his long and productive research, he worked exclusively with colors provided by light. The light revealed in the color without playing with color transmits an ethereal state within the space, elevating their interactions. The research started in the 70s was recuperated in the following decade in which Lisi makes use of a precise and circumscribed iconography in which various vertical strips of light intertwine at the center of the painting, intersecting and branching out in as many luminous rays. As in all of his works, the Metacrilati are the result of a multiform process that started outside of the studio, but they reach their most intense stages within it. The artist drafts pools of pigments and mediums that in turn become places for the creation of expressive signs, traces, and sediments. He circles around his works, moving around them as required by the evolving compositions, setting himself between the visual rhythms and their textures in incredibly real terms. The painting, like the Tiber river and the forest that surrounds the Roman countryside, offers infinite opportunities for immersion in the warm light enveloping the city. As visual and metaphysical focal points, the Metacrilati are immersive and enigmatic objects focused on presentation. The ability to take advantage of natural energies is translated with peculiar stretches of light and color that respond to a multitude of factors in real time: environmental conditions in the visual space, the position of the viewer’s body, the psychological qualities and the philosophical considerations that are inseparable from perception itself. The artist always moved in a state of consciousness in which an innate spirituality was sharpened by a robust rationality. In this intellectual magma he increased, in the late 1980s, the range of his color combinations and applied the visual textures to his procedural rigor. He utilized an even more diversified tonal range and created combinations and intensities that he planned and sharpened to make hypotheses about energy and color, which informed his artistic career from the beginning. Every work in the series represents a concentrated expression of formal and intellectual clarity in the midst of the expanding complexity of the cosmos. This idyllic state is elevated and integrated by the interaction with the permanent collection in the Museo dell’Arte Classica, revealing its temporal dimension, esthetically assimilable and malleable in the intertwining of the dynamics between artworks from different time periods. The exhibit includes a group of unreleased free canvases, Segno (1994-1997), Gesto (2000-2001), and Segno aperto (2003-2005) hung between the walls, forming an ethereal installation composed with cables strung on the sides of the museum walls. By altering the usual narrative, viewers immerse themselves in the visual encounter in an ephemeral and ineffable combination. As synaesthetic fields of shape and color, the canvases are described in tactile and emotive terms that escape all rational logic and are unique to every viewer. Since their formal attributes function as visual hooks, the eye is attracted in the atmospheric spaces of their compositions before encountering an apparently unlimited number of associative openings. The worlds take shape rapidly through their various surfaces, disappearing again in the same manner exactly when the act of seeing generates an optical overload or a disruptive dissonance. The accumulation of Lisi’s signs reveal recognizable traces of planning and elaborate negotiations with the material, transporting the viewer towards the concrete reality of the pigment, of the medium, and of the surface. In this cathartic state, the artist makes space for both precision and abandon, inviting the viewers to participate in processes of controlled creation and project themselves in this state of contemplation. Together, the art in the exhibit fall into a body of work capable of exploring new chromatic relations and the most ample range of transparencies, signs, and luminosity. As in all types of research with a vast reach, the dimensions, the form,